I have a memory from when I was around 8 of my mother and me going to Dairy Queen on the Cape. After we grabbed our cones of vanilla soft serve, we walked out into the hot afternoon air and, as if a coming-of-age ceremony, my mother proceeded to teach me how to properly eat the treat. Under an umbrella, she told me to take my ice cream and let it sit in the sunlight for a few moments. In the sun, I watched as the ice cream’s exterior quickly soften and begin to glisten. When it looked like the soft serve was about to melt out of the cone, my mother told me to take a taste. Circumventing around the melting soft serve, I was in heaven, reveling in the magic of the sweet velvety ice cream on my toung. When i finished my first lap around the cone, revealing its cold interior again, I understood the lesson- melt & enjoy – rinse and repeat.

While I practiced the newfound skill, my Mother told me that when she was a kid, her and her friends would go to Dairy Queen every once in a while, and pay 5-10 cents for a cone. “One nickel!!” I exclaimed, “why did you not get an ice cream every day – or multiple times a day!” I thought out loud, “if ice cream cost a nickel now, I would get a cone every hour!”.

Fast forward 20 years, and I find myself in Hanoi, riding around the city on my motorbike, hopping from one ice cream shop to the next. There’s an chain called Mixue, and and it sells ice cream 10,000 Dong ($0.42) a cone. Its all over the city, and I eagerly rush from one Mixue to the next, picking up 42-cent cone after 42-cent cone, exhilaration coursing through my veins. I have the feeling of getting away with something – as though this wonder shouldn’t be so easy to get – and for so cheap. “

“Its just like Dairy Queen with Mom”, I think.

Joking, I say to myself, “Its just like America here, having a fast food joint every other block” “the TRUE American dream, right here, across the world – at the heart of The Socialist Republic of Vietnam.”

And in that moment, I was forced to contend with the complexity of the Communism, what it really meant to be in a socialist state in 2023, and how it differed from what I was taught throughout my life in the US.

What does it really means to be in a communist state?

How is a world under a communist regime truly different from what I experience at home?

Why did we, as Americans, waste so many lives trying to prevent this?

It certainly isn’t because Kissinger was afraid of the rise of Mixue, (although I will admit that in my research I found out Mixue is a Chinese franchise – so maybe the fight would still be worth it to him now)

I found that coupling my time in Vietnam with Bao Ninh’s book, The Sorrow of War, which criticizes each party involved in the Vietnam War – the US military, the People’s Army of Vietnam (North), and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (South) – I established an understanding (albeit incomplete) of the conflict that balances the immense complexity of the conflict.

The Sorrow of War is a 1991 novel written by Bao Ninh as his graduation project at the Nguyen Du Writing School in Hanoi. The novel tells the fictional story of a soldier who is collecting dead bodies of fallen comrades for reburial after the anti-American Vietnam War. Throughout the novel, the soldier begins to consider his past time in the army during the war. The novel won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize and was banned until 2006 by the Communist Party of Vietnam.

The novel depicts his sympathy for his comrades who died in the war and those who parted from their loved ones in the conflict. It also offers Ninh’s thoughts on the psychology of young people who were born during the war.

There wasn’t much I could find on Ninh, but the introduction says that Ninh himself was born in Hanoi in 1952 and served with the 27th Youth Brigade. Of the 500 who served with the brigade in 1969, he was one of 10 who survived. In Ken Burns’ 2019 documentary on the Vietnam War, Burns had the opportunity to interview Ninh, who argued that the Vietnamese people who fought against the Americans were not specifically fighting for Marxism, but rather fighting to bring peace for their country. Nonetheless, in his novel, Ninh offers a complex understanding of the conflict – offering an illustration of American aggression, as well as atrocities committed by both the North and South Vietnamese armies to their fellow people.

One of my favorite quotes from the novel-

“A human being’s duty on this earth is to live, not to kill – taste all manner of life – try everything. Be curious and inquire for yourself. Don’t turn your back on life”

Sorrow of War, Bao Ninh

It would take months to write out a history of the war and how colonialism, US interventionism, and internal strife led to the Vietnam War, and I do not claim to have a comprehensive understanding of the conflict – so here I will just share the perspectives I was offered during my time in the country.

Interestingly enough, my first perspective of the Vietnam War came from a firmly pro-American Vietnam War veteran of the South Vietnamese Army, who was my tour guide for the Cu Chi Tunnels. While he did not speak much about the North Vietnamese soldiers themselves, he spoke out against the current Vietnamese government and made a point, multiple times, to thank me for the US soldiers who sacrificed their lives in the Vietnam War.

To be honest, hearing his perspective initially had my head spinning. Prepared for a tale of resistance to American aggression, I struggled to wrap my head around his pro-American sentiments. It wasn’t until I spoke to him privately after the tour that I was able to get a fleshed out understanding of his perspective. After the Americans withdrew and the North took over Saigon, our tour guide was arrested and imprisoned for 5 years by the North Vietnamese Army. For decades, he struggled to get freedom from the state, and felt as though he was heavily censored. His saving grace was a business autonomous from the state, who took him in as an employee, protecting him from harassment and persecution. While I cannot corroborate his perspective, I could tell from the way he spoke to me that he was still struggling with what happened in the 1960’s and 70’s – and his honesty was profound.

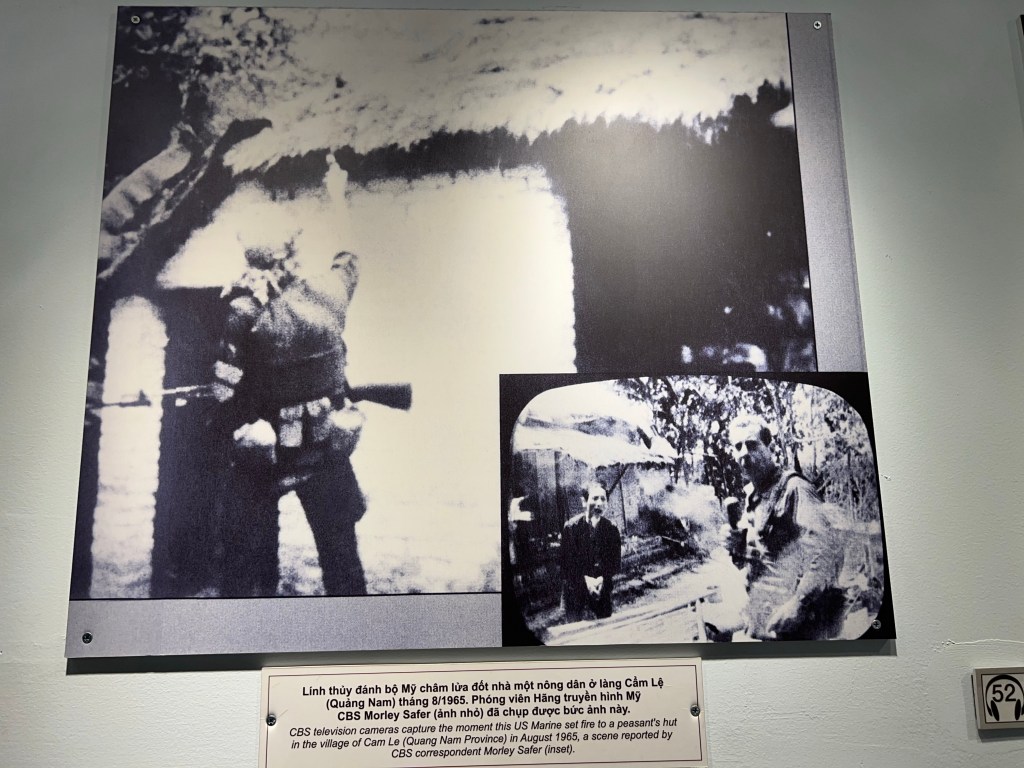

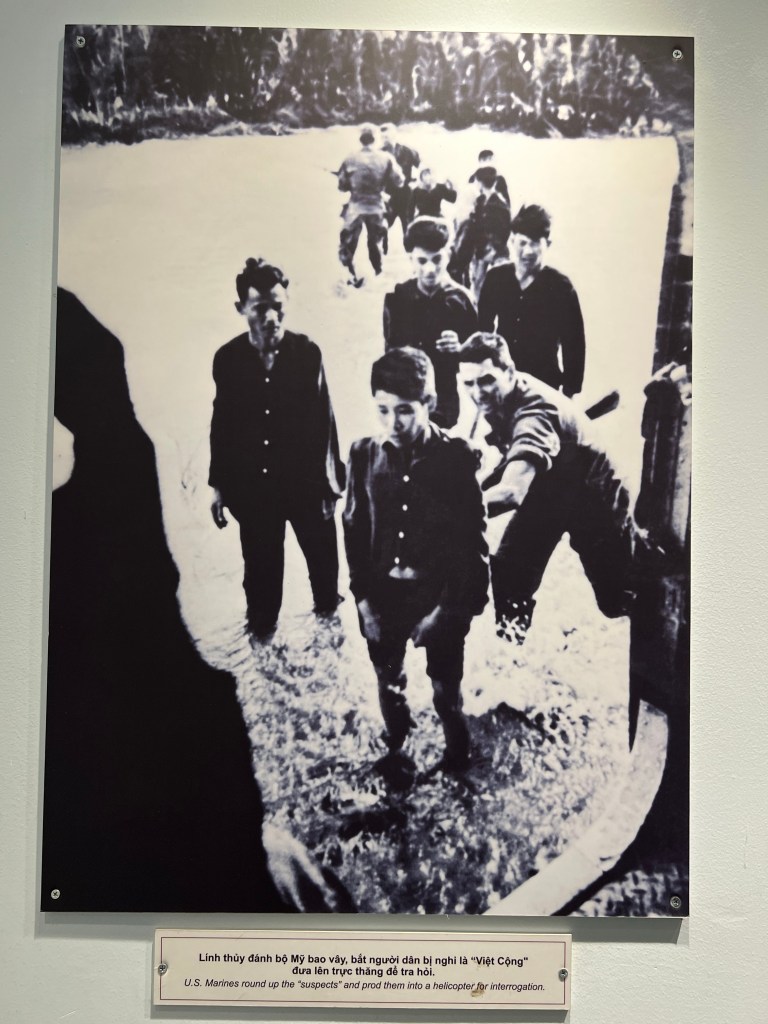

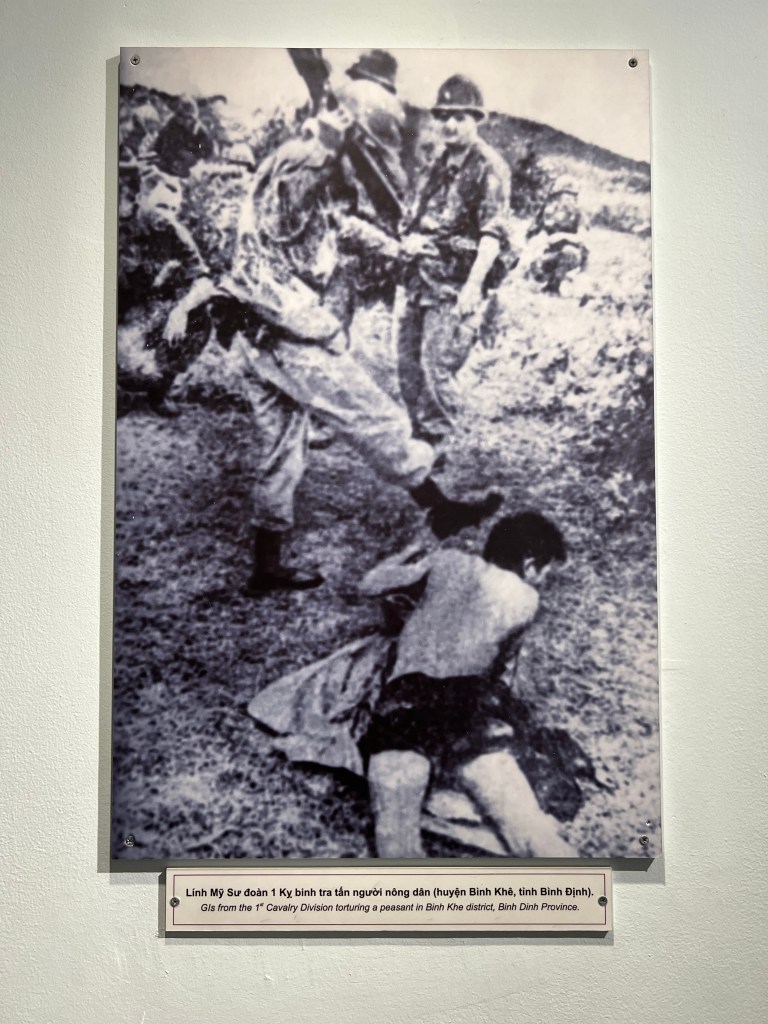

A few hours later, I headed to the War Remnants Museum, and was given another perspective of the conflict from the North’s perspective. It told a history of American-Saigon prison camps designed to torture, humiliate, and murder pro-liberation forces. It spoke of Saigon’s murder and kidnapping of pro-socialist patriots and the atrocities committed by the US military.

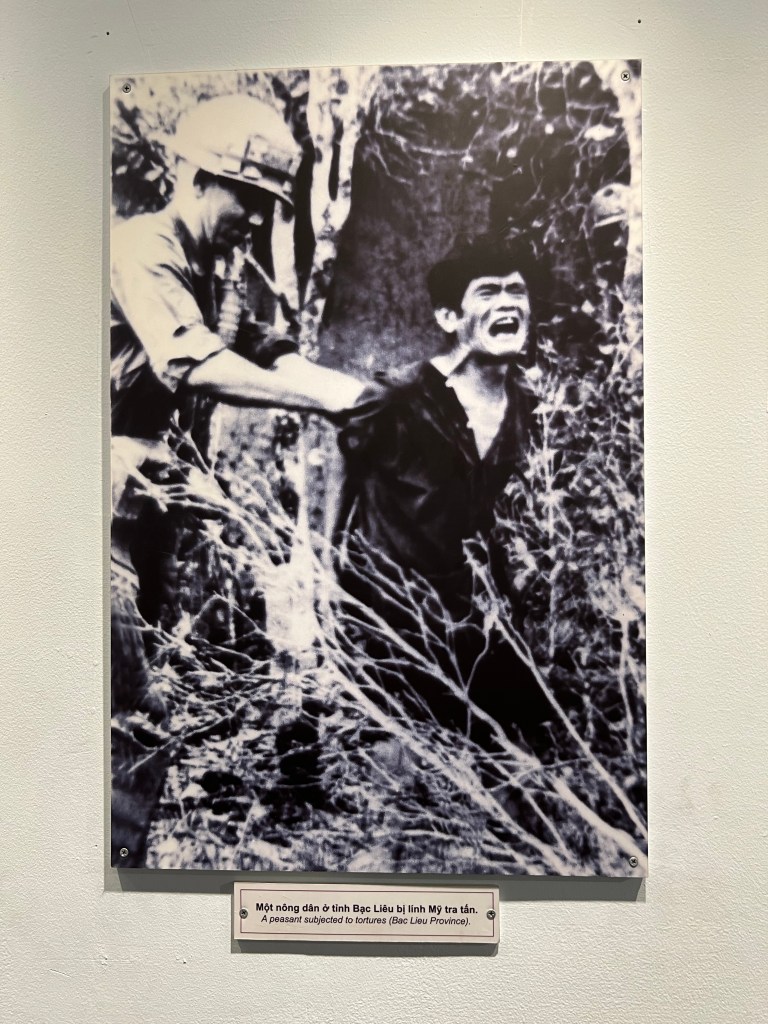

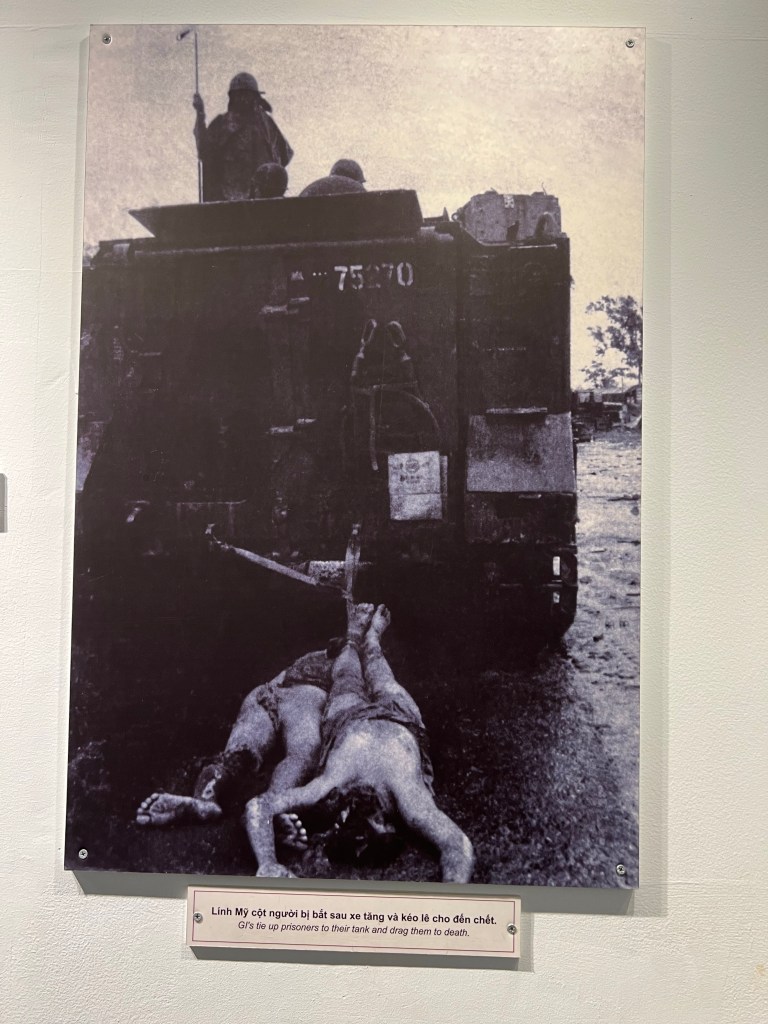

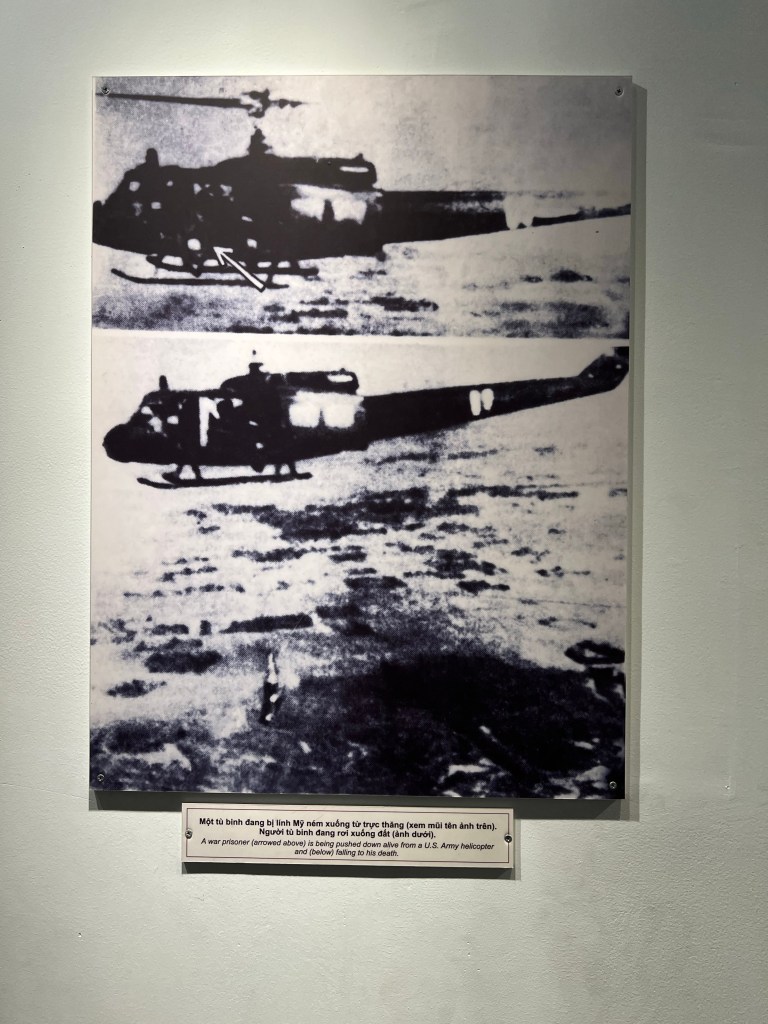

At one exhibit, there was a large ceramic vase. To the left, a placard told a story – A Vietnamese family was found by a group of US soldiers, and the three children hid in the vase while the rest of the family pleaded with the Americans to let them be. Instead, the soldiers went to the vase, shot the three kids, and burned down the family’s home. Another exhibit told the history of the My Lai massacre, the mass murder of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians by US troops in 1968. Photo evidence of US military violence covered the walls – soldiers pushing prisoners out of flying helicopters, dragging North Vietnamese soldiers to death with trucks, burning civilians and their homes with napalm – it was all very hard to look at. Yet another exhibit showed the effects of Agent Orange used by the US government as a way to starve out VC – resulting in generations of physical and mental defects in future children. It told the perspective of Ho Chi Minh and his government, as they navigated a civil war and American aggression.

The museum did an incredible job of documenting the horrors of the war and American aggression in the region – but it did seem to feel one-sided and left out the violence committed by the Ho Chi Minh government, such as with the “class struggle campaign” – however some may argue this was in reaction to French and later Japanese colonial occupation.

The conflict is quite complex and I think it will take me a long time to really grasp it; however, what is clear to me is that the United States should have never been involved – and its choice to support the South Vietnamese government, particularly through military support, led to the needless destruction of thousands of lives. It is a shame, really, that this is part of my nation’s history – but I am grateful for how Vietnam accepted me despite it.

After I finished the War Remnants Museum, I went to a cafe to decompress. There, I saw a 20-something year old Vietnamese engineering student, Son, who I met earlier in the Museum ticket line. Son asked if he could sit with me and we started discussing the museum. Out of the blue, he asked where I was from, and I, uneasy and shaken, said I was an American. Son sensed my discomfort and quickly offered me a life raft. He said he didn’t blame me or the American citizens for what happened – rather the government officials that authorized it and the soldiers who took advantage of the situation. He went on to say that he was quite fascinated by the US and hoped to visit its famous state parks one day. We ebbed and flowed between talking about the museum and our lives but what stuck with me most about our conversation was how determined Son was to look forward- to balance both the burdens of the past with an eagerness for a better future. He didn’t want to forget what happened in his country, but he didn’t want to let it control him either.

It is immensely inspiring to see how the Vietnamese people have navigated their lives and the world despite the atrocities we committed in their country. My trip has shown me a nation of vibrant people determined to create a better life for themselves and their families – and no one, not even the US military, is going to stop them.

Sam