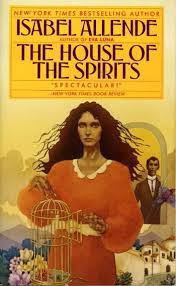

The House of the Spirits is the debut novel of Isabel Allende, published in 1982 after a stream of rejections from Spanish-language publishers. Similar to One Hundred Years of Solitude, Allende’s novel became an instant best-seller, being named ‘Best Novel of the Year in Chile’ the same year it was published in Buenos Aires. The idea for her book came from the death of Allende’s 100-year-old grandfather, in which a letter she began to write to him before his passing became the manuscript of her novel.

Allende was born in Lima, Peru, in 1942, moving to Chile in 1953. She is the daughter of a first cousin of Salvador Allende, President of Chile from 1970 until his death following the 1973 military coup.

In 1973, after the overthrow of President Salvador Allende in a coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, Allende began arranging safe passage for people on the ‘wanted lists’. When she was added to the list herself, Allende fled to Venezuela, where she lived for 13 years and wrote The House of the Spirits. Allende moved to California in 1988 and became an American citizen in 1993.

Fun Fact! In 2014, President Obama awarded her the presidential medal of freedom

Funnily enough, Allende’s novel was heavily influenced by Gabriel Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, something I did not plan when I chose the two books for the book club. As a sort of homage to Marquez, Allende’s story depicts the timeline of four generations of the Trueba family, navigating post-colonial society in Chile (from around 1910 through the early 1970’s). Similar to Marquez, Allende uses hers childhood and personal experiences (particularly under the Pinochet dictatorship from 1973 to 1990) as a historical basis for her novel.

Through elements of magical realism – Allende weaves a story narrated by Esteban Trueba, and his granddaughter, Alba, who organize the journals of Esteban’s wife (Alba’s grandmother), Clara del Valle, into a history of the family.

Over the course of four generations, The House of the Spirits navigates the social divide between the “civilized” and the “barbarians” (peasants), the clash between social classes, and the influence of women in society.

I was particularly compelled by the character of Estaban, and how Allende chooses to portray his complexity and his eventual passing at the end of the novel. An obsessive, violent, and materialist conservative, Esteban spends much of the novel focused on becoming rich and powerful. He owes most of his success to his family name and the labor of the peasants at Tres Marias, but he never treats them with respect or equality. Quite the opposite – Estaban actively oppresses them – preventing them gaining an education, and, eventually, denying them workers rights and political representation. He goes as far as to advocate for the military coup of the unnamed socialist Chilean President to protect democracy and conservative values. As he ages, Esteban begins to see the consequences of his selfishness and violence, becoming more and more isolated from his family and friends. At the end of his life, Estaban only has his granddaughter, Alba, as a companion – void of the many family and friends that surrounded him at the beginning of the novel.

Despite this, Allende chooses to have Estaban die happy, his granddaughter, Elba, by his side as he hallucinates love and forgiveness from his estranged and long-dead wife, Clara (it is possible this is her spirit and not a hallucination, but it is not clear one way or the other).

I have mixed feelings with this conclusion to Esteban: on the one hand, I appreciate the idea of a hateful man at the end of his life finding redemption; on the other hand, it’s hard for me as the reader to forgive Esteban after all the violence I witnessed him commit. Further complicating things – Alba, the narrator of a majority of the family history, is presumed to know of all of the violence and abuse Esteban has committed – and yet she chooses to love and care for him anyway.

In this conclusion, the story forces the reader to decide: is Estaban the classic villain we are meant to reproach or (more interestingly) a victim of the experiences that lead him to who he is. Furthermore, we must decide where we, ourselves, fall on the spectrum of forgiveness after mistreatment/abuse. Do we villainize and ostracize in order to protect ourselves or do we forgive and feel sorry for the perpetrator – as they also harm themselves when they hurt others. It reminds me of the psychology of bullying – harming and humiliating others who are vulnerable – a result of unresolved past trauma, cowardice, and a desire for revenge. Of course, it is important to stop bullying, but I also think there is room for sympathy for the pain that fuels a bully’s actions.

I think I fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. While I think it is unproductive to “forgive and forget”, I think there can be a balance between protecting yourself and providing for the perpetrator, who is a victim in their own right. I will caveat this statement by saying that I don’t think forgiveness is always the right path. There are many cases in which its not fair to place that responsibility onto the perpetrated; but, I think it can work in cases where the perpetrated is in a strong enough position to be both the victim and the healer.

While I think there is a lot more to say – particularly in class struggle, historical context, and the role of women, I will leave it there because I am out of time! Please let me know what you thought of the book!