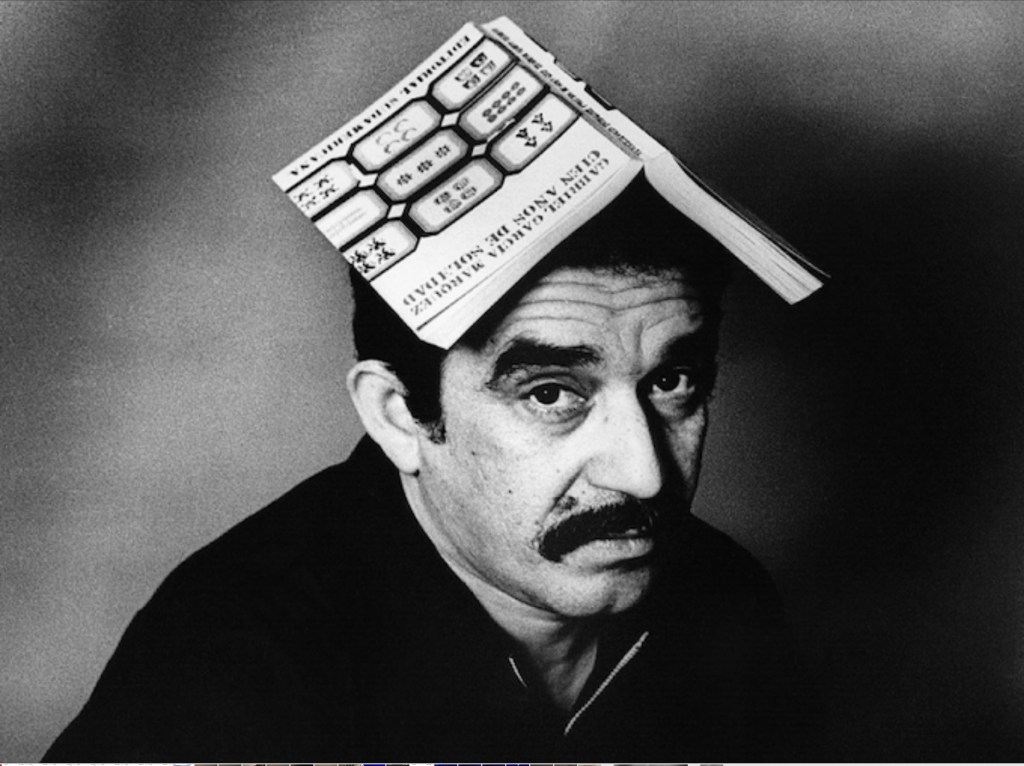

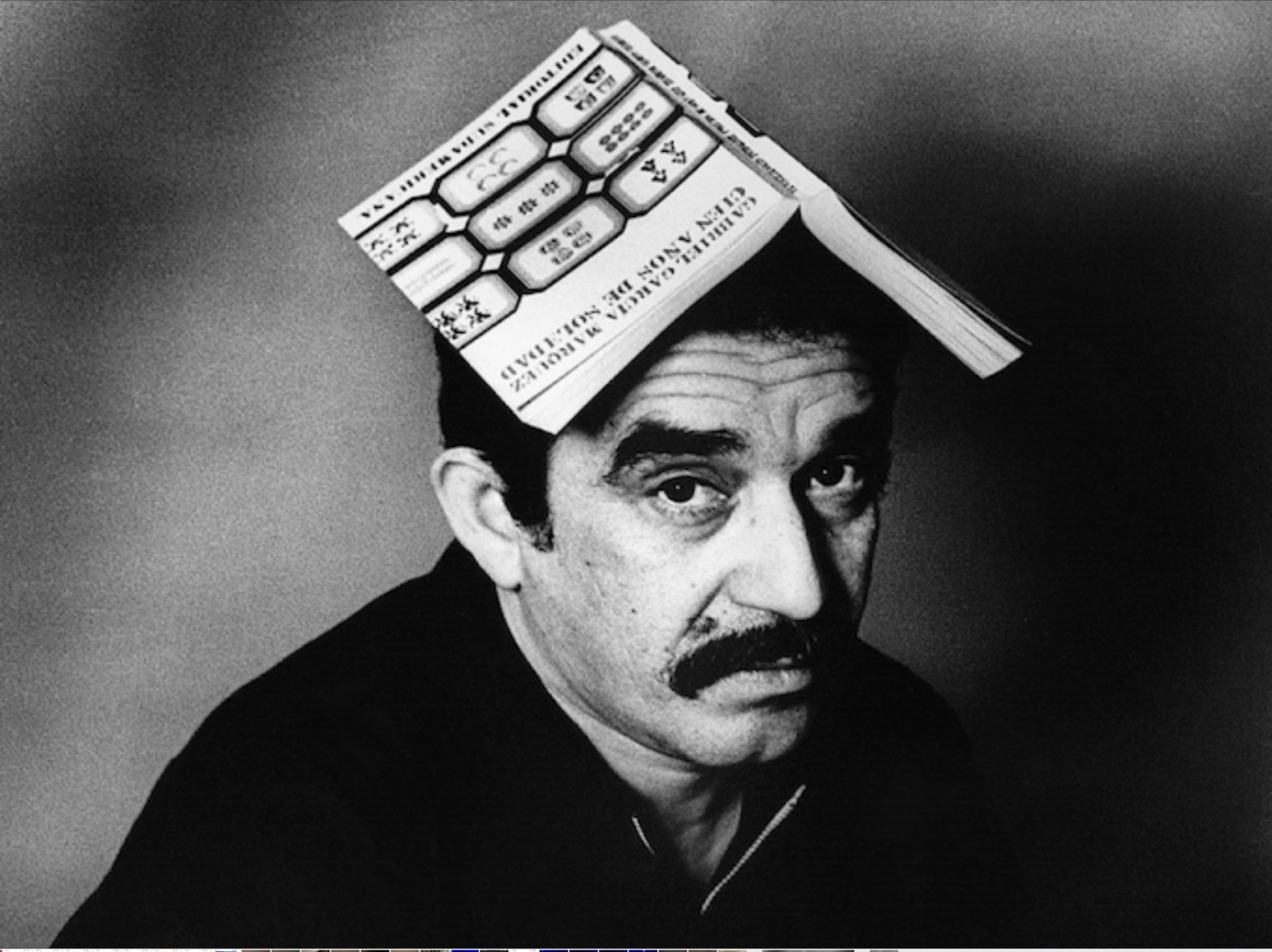

First published in Buenos Aires in 1967, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude follows the lineage and events of the Buendia Family through the founding, transformation, and eventual collapse of the mythical village-city of Macando. Written in just 18 months while Marquez was in his early 40’s, One Hundred Years of Solitude became an immediate best seller in spanish with nearly half a million copies sold in its first 3 years. In 1970, Marquez’s novel was selected as one of the best 12 books of the year by Time magazine and since then has sold over 50 million copies in 46 languages.

Throughout this fictional account, Marquez emphasizes the significance of the repetitiveness in human existence and the eventual becoming and ending of things. Taking place in a region of Colombia roughly between 1820-1927, the story integrates historical elements of political violence, the effects of dictatorship, and colonization – influenced heavily by Marquez’s own experience growing up in the 1930-40’s. Through the Buendia family (who’s lineage is the main story of the narrative), Marquez shows the personal impact of these historical elements, and how human nature – passion & love, eroticism, power-yearning, and irrationality – further complicate human existence.

Through the voice of an omniscient narrator, the reader is told about the life of six generations of the Buendia family, as they witness the founding of Macondo and participate in its rise, fall, and eventual destruction through civil wars, foreign capitalist ventures, and personal strife.

While there are, of course, many possible take-aways from this story, I was most moved by the subtle sense of mourning I felt throughout the fictional history, as I observed the birth, growth, and eventual death of most of the characters. I felt dichotomy of emotion – on the one hand, saddened by the eventual loss of each character (which I began to predict as the story progressed); on the other, moved and heartened by the rapidity of change presented in the story – much of which was positive. From my vantage point as the reader of this ~100 year history, it was powerful to observe the significance of time in the creation and destruction of people and place.

I believe the concept of change with time was quite applicable to my time in Colombia these past 2 weeks – in the way it informs some of modern Colombian history and the power of time in societal transformation.

Last year, as I began to create my travel itinerary, whenever I mentioned Colombia I was confronted by 2 starkly different reactions. It seemed that many of those born before the 1980’s had an understanding that Colombia was a very dangerous place, full of gangs, drugs, and poverty. While I believe that, as with any country, concern is valid, I found it interesting that the Colombia Americans knew of in the 70’s 80’s, 90’s, and early 2000’s is far from the reality of the Colombia I witnessed during my trip. Through the course of my travels, I saw a booming coffee industry (one of the most highly respected in the world), safe and compelling urban centers, and a robust tourism industry. And from what I learned in the tours and conversations I had with locals, Colombians have transformed their cities and neighborhoods into bustling metropolises, full of growing opportunity and national pride.

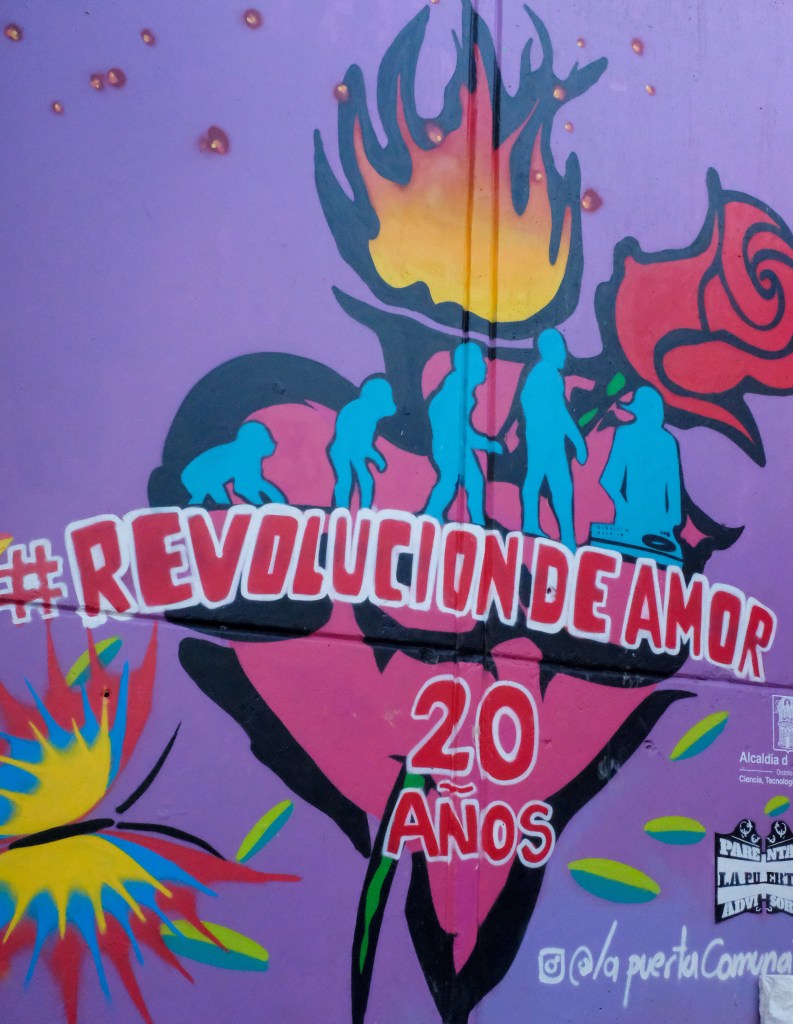

One neighborhood in Medellin, Comuna 13, demonstrated this brilliantly to me. In the 1980’s-1990’s Comuna 13 had such a high murder rates it was considered the most dangerous place in the world. Now, it is now one of the safest and most explored areas in the city, famous for its powerful graffiti art and murals where young people express themselves through depictions of conflict, corruption, and the power of community action which helped bring an end to the violence. On a graffiti tour, I was able to explore the neighborhood, just 6 years after the peace deal between FARC and the Colombian government. While on the tour, I had the opportunity to meet Don Angel Ivan Gonzalez, who was pivotal in the revitalization of the Vicente de Julio area in Comuna 13, which is now one of the central art hubs of the city.

Ivan lived in Comuna 13 most of his life, witnessing the violence that took place in the neighborhood – gang killings, abductions, and the notorious interventions conducted by the Colombian state that resulted in the indiscriminate maiming and killing of hundreds of civilians (you can learn more about the operations HERE). Despite experiencing decades of strife, Ivan maintained a steadfast commitment to supporting his community. Ivan helped establish the orange-roofed escalator, finished in 2011, that allows Comuna 13 residents to scale the mountainous neighborhood in six sections, with a journey taking just six minutes. He also played an integral role in cultivating the art-scene that has made the neighborhood so famous, promoting youth initiatives that encouraged expression through art.

It was incredible to see how much change someone can bear witness to in just one lifetime – and how much of an impact one individual can have on the growth of a community.

Of course, progress is not linear – just 2 months ago, 6 Colombian soldiers were killed in a FARC dissident attack. Violence is still an element of Colombian life and economic opportunity continues to be a challenge for many. But the improvement of the lives of Colombians is obvious – in the tourist-centered experiences I had and the candid conversations I had with locals – and it is incredible that this momentous transformation took place in such a short period of time.

One Hundred Years of Solitude and the mythical town of Macando are, in part, a depiction of the reality of Marque’s own experiences, in which he witnessed the consequences of neo-colonialism and state sponsored violence as he grew up in Aracataca. The fictional town of Macando and Marquez’s hometown hold many parallels – both experienced foreign fruit companies that brought prosperous plantations to nearby locations – both towns faced long, slow declines into poverty and obscurity. Both Macando and the Colombian port city of Santa Marta faced a massacre of plantation workers striking against unfair working conditions – and both regions face a war between conservative and liberal ideologues.

While Marquez’s experiences with political strife, poverty, and violence culminated in the perceived decline that he represents in Macondo, Ivan represents to me a reversal of such experience. He demonstrated the next generation of societal change – from the decline Marquez witnessed, to the powerful rejuvenation Ivan helped usher in. For both Marquez and Ivan, time played a significant role in the transformation of space – but unlike Marquez, Ivan has the opportunity to represent progression through the conjunction of time and strong public will.

To anyone who has an interest in experiencing a nation full of community & pride, wonderful coffee & fried food, great music & dance, and perpetually clean bathrooms, I strongly recommend you consider visiting Colombia.

One thought on “Travel Bookclub I: One Hundred Years of Solitude”